I need to warn anyone who might be considering reading this article that it contains swearing and disturbing imagery. The same may be true of my books, but as fiction, we can go to bed and sleep at night, knowing that none of it is true. This article, however, is a recollection of events from my past.

Now that you’ve been forewarned, the choice is yours … to read, or not to read.

Mum went off the rails every six or seven years. I thought this was normal, until I was in my early teens, and no one else talked about their mother’s strange behaviour.

I can clearly remember visiting Mum at the Royal Park Psychiatric Hospital, the first time she had been hospitalised. The patients scared my seven-year-old self. Mum scared me even more. Once she was holding a piece of paper with our address on it, and asked if that was where she lived. Another time she told us that a patient had thrown another patient into a scalding hot bath. After that, Dad told my sister to play with me outside, in the hospital grounds, while he visited Mum.

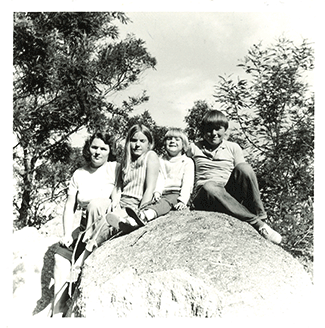

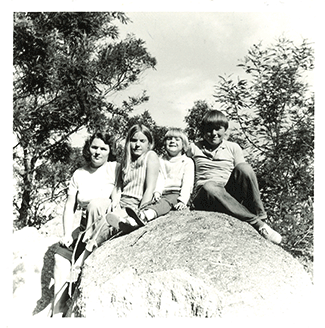

Mum and we kids at the You Yangs

Mum was hospitalised again, shortly after my 21st birthday. She had embarrassed me at the small gathering we had by talking about “Vitamin C! Vitamin C!” and telling everyone, “All your father wants to do is fuck, fuck, fuck!” She was committed after she knocked a child off their bicycle, for riding on the footpath. The police came and took her away in handcuffs, as though she were a common criminal. I did not visit her. I didn’t even ask what facility she had been taken to. All I wanted to do was to get away from her, and the craziness she represented. I just wanted a normal life.

It wasn’t until I had my heart ripped from my chest that I learned the truth about Mum. I was twenty-four at the time, and Mum was off the rails again. Mum and Dad had moved to Hoppers Crossing, at Mum’s insistence, to be closer to her children. It was a twenty-minute walk from their place to mine and Mum walked over to visit me one weekend. I was home alone, so had no backup, and as the car was parked out the front she knew I was in. I decided that I’d tell Mum I was on my way out, and head off to the local shopping centre. I’d wander around the shops for a little while before going home. The best laid plans, as the saying goes … I ended up cornered in my laundry, with nowhere to go. Mum was ranting about how someone should put Barbie in a coffin and bury her, and that all the dead people in the cemetery were lucky. I can’t quite remember how I extricated myself from that situation. I knew she loved me deeply, and that she lived for her children, but that didn’t stop her from scaring me when she wasn’t stable. It’s a sad fact that the memories that are burned deepest into my brain, and rise to the surface regularly, are the traumatic ones.

One night, Mum rang and said, “I have a knife for your father!”

It never one occurred to me to call the police. Instead I rang my brother. I don’t remember if he picked me up or if we met at Mum and Dad’s house — that sort of detail isn’t important anymore. We didn’t ring the doorbell. Instead we snuck around the outside of the house, via the side gate. There was a light on towards the back of the house. We crept to the window and peered in. Dad was sitting there watching television. Mum was nowhere in sight. One of us tapped on the window to attract Dad’s attention. Luckily for us Mum was hard of hearing, and refused to wear hearing aids, so she hadn’t heard the noise. Dad opened the window and we talked for a few minutes. Yes, he was okay. Did he know that she’d said she had a knife for him? No, she’d been waving a knife around, but hadn’t said it was for him. No, he didn’t want to leave. He would simply stay out of Mum’s way until she had calmed down. As my brother and I left, as quietly as we could, another light came on. Mum yelled through the window, “Tell him he’d better stay away.”

The last time I saw Dad alive was two days before he died. Mum was out, so I went to visit him. She had told me, a few weeks before, that Dad hadn’t wanted me. I knew that wasn’t true, yet I felt I had to tell him what Mum had said. I told him I didn’t believe it. If I’d been unwanted, surely I would have known? We may have been a dysfunctional family, we may not have hugged much, or said the words, “I love you,” out loud, but I’d always felt loved. I asked him how he could put up with it, and why he didn’t leave. He told me that she was a good wife and mother. Just as the thought to call the police had never occurred to me, the thought of leaving Mum had never occurred to him. I told him that if it was me, I wouldn’t hang around, and that he was welcome to come and stay with me if he wanted to. I never said those words — I love you — before I left. I never got to tell my Dad how much I loved him. The next time I would see him, he would be lying dead, on the floor near the kitchen table, the hint of a smile on his face. On the table we would find his favourite cup and saucer, an opened bottle of vodka and an empty bottle of pills.

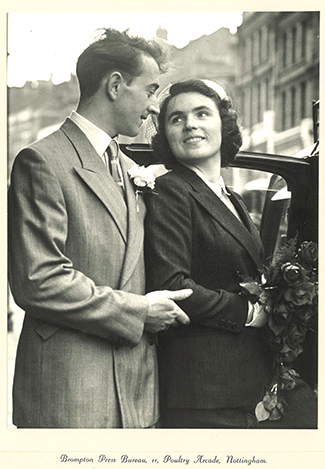

Mum and Dad on their wedding day

Mum had gone on a day trip to Ballarat, but she’d caught the wrong V/Line train and ended up in Geelong. Some family friends — my sister’s in-laws — who lived in Geelong drove Mum home. They found Dad. He was already dead. Mum’s next door neighbour rang me at work to say there was an ambulance at the house, and to ask if I could I come home. I remember clearly asking her if they’d come to take Mum away, and that it was about time. “No,” she said. “Your dad’s dead.”

It was a surreal experience. I rang my brother’s house, but he was at work. I’m sure, in my anguish, I told his wife what had happened before hanging up and ringing my brother at work. The next phone call was to my husband. It was his day off. I asked him to get his butt over to my parent’s place as soon as possible. My sister was living in New Zealand at the time. I can’t remember who called her — me, my brother, or her in-laws — or when.

I car-pooled back in those days, and it was my turn to drive that week. Rather than leaving my friends in the lurch, I left them the keys to my car. My brother drove from Altona to Footscray, to collect me, and together we headed back to Hoppers Crossing …

By the time we arrived, the ambulance had already left. Dad was still on the floor. My husband was sitting next to him, holding his hand. I couldn’t look at Dad. I had to leave the room. Eventually someone arrived to take his body away. I watched as the plain, white van drove my Dad’s body away. I felt cold and detached … numb. I don’t think I ever truly recovered from that experience. I have built a hard shell around what was left of my heart — a heart that has been ripped out is never the same again, even when great care is taken to put it back where it belongs. Only on rare occasions do I let something, or someone, get in. In later years my husband would refer to me as a cold-hearted bitch, an ice queen. To some degree, that was true.

In the early hours of the morning Mum rang and told me that she’d found a note from Dad. Once again my brother and I found ourselves in the house where, not too long before, my Dad’s cold, dead body had been lying on the floor, to read the note for ourselves. It said, “I’m sorry.” Dad had left it under his pillow, along with his wedding ring — the note was later handed over to the police. Mum didn’t seem overly upset, but she said she wanted to go to hospital for a while, and we agreed that it would probably be a good idea. The next day we headed to the Saltwater Clinic in Footscray. It was there that we found out Mum had bipolar. It was there that we learned that every few years she would think there was nothing wrong with her and go off her medication. Dad had not wanted us to know what was wrong with Mum, but it would have made it easier to understand why she behaved as she did, and provide him with much-needed support. The psychiatrist had Mum admitted straight away. He warned us that if she went off her medication again, she may blame herself for Dad’s death.

Mum stayed at the psychiatric unit of Western Hospital until the funeral, which was ten days later. As Dad had died under suspicious circumstances the coroner was required to perform an autopsy. At the viewing I can still remember seeing the cranial incisions that had been made to provide the coroner with access to his brain, for weighing and whatever tests were deemed necessary. I also remember seeing his fingernails, which looked black as a result of blood that had pooled in his fingers. I visited Mum once while she was in hospital, but found it difficult to face the person whom I believed was responsible for the death of my father.

Seven years later Mum went off her medication again. The psychiatrist was right. We knew she needed help. When I called the Saltwater Clinic they told me that unless she was suicidal, there was nothing they could do. Two days later, Mum was dead. She had chosen the same path as Dad. It was a relief, really, to know that she had found peace at last.

I still blame Mum for Dad’s death, but forgave her long ago. There are times when I wonder if I played some small part in it, telling him what Mum had said about him not wanting me. Did that push him over the edge, thinking that his youngest child, his ‘kleine zwiebel’, might doubt his love for her? I guess I’ll never know the truth of it. All I can say is, “I love you, Dad.”

To learn more about bipolar disorder, visit https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/bipolar-disorder

12

Didn’t want to read and run. Heartbreaking.